Frankovka modrá, often known as Blaufränkish, is the most widespread red grape variety in Central Europe. Bla, Bla …. common phrase, everyone repeats it.

But do we really know Blaufränkish?

How is it possible that a variety with the obvious potential of the global elite is so unknown to both professionals and wine lovers?

Does Blaufränkish have the real potential to be one of the great grape varieties?

For answers, we must look to the past and at the same time understand the context of Central Europe.

According to the latest DNA research, Blaufränkish is a clearly indigenous variety native to the Pannonian Basin, but we know very little about its origins and still do not know the exact reason why it spread so massively at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries in Central European vineyards. Historical resources are limited and relevant facts often converge with legends and myths.

Nevertheless we would like to reconstruct its history and place it in the context of Central Europe. Today, the term Central Europe means the states that were formerly located in the central part of the Habsburg Monarchy and the subsequent Austro-Hungarian Empire. Specifically, they are: Austria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Slovenia and Croatia.

These countries have a rich common wine-growing tradition, and a common historical, social and cultural identity closely linked tothe fate of the aforementioned Empires.

You will read in the article:

- Blaufränkish, is it Pinot Noir of Central Europe?

- The Empress of Central Europe, heritage of the Habsburg Monarchy.

- Climatic factors affecting the Pannonian Basin

- Origin of the name Blaufränkisch

- The Little Ice Age, Ottoman occupation and 30 Years’ War

- The first mentions of Blaufränkisch

- The official genetic origin of Blaufränkisch

- Phylloxera and Blaufränkisch

- The modern history of Blaufränkisch

- Grilled goose breast and Blaufränkisch from Tekov

Panonian Basin

At the outset, it may be useful to describe the Pannonian Basin a bit to better understand the natural conditions in which Blaufränkish was born, but also the political, economic and cultural history of the region which also had a significant impact on its expansion.

The Pannonian basin is a large depression with an area of 200,000 km², bordered by three mountain ranges. It is bordered by the Eastern Alps in the west (~ 2000 m.n.m), in the north and east by the Carpathians (~ 1500 m.n.m) and in the south by the Dinaride Mountains (~ 1000 m.n.m). The border between the Alps and the Carpathians is formed by the river Danube, which passes through the middle of the Pannonian Basin. The plain’s water empties into the basin.

Most of the area consists of lowlands at an altitude of about 100 m above sea level, from which rise lonely, isolated mountains and highlands. The Pannonian Basin lies on the territory of today’s Czech Republic, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine, Romania, Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia.

Climatic factors affecting the Pannonian Basin

The Pannonian Basin is located in a moderate climate zone with a regular alternation of four seasons. There are three main climatic influences interacting at once:

- Oceanic: The Pannonian Basin is about 1,000 km from the Atlantic Ocean, and western currents bring precipitation and humid ocean air that mitigates temperature swings.

- Continental: The continental effect, on the other hand, is manifested by more pronounced temperature differentials, which mean warm, sunny, dry summers and cold winters with low total precipitation. The continental Arctic air from the northeast flows in col, dry, and stable layers in winter.

- Mediterranean: The Mediterranean influence in summer from the south brings mostly dry and warm air, which is manifested by dry, and warm to hot summer weather. In winter, on the other hand, relatively cold and humid air full of precipitation can occasionally enter the Pannonian Basin from the Balkans.

As a result of the alternation of the above three climatic influences, there is a mosaic of small wine-growing regions with diverse climates and characteristics in Central Europe.

The Habsburg Monarchy

In the case of Central European wines, it is often forgotten today that before the First World War, the Pannonian Basin was united under the constitutional dualist monarchy called the Austro-Hungarian Empire since 1867 and had a rich viticultural and winemaking tradition. As an example, the empire was the first to adopt comprehensive legal norms governing all stages of winemaking – a viticulture act on July 21, 1880 – with an emphasis on the quality and safety of the final product.

Blaufränkisch is even a clear legacy of the earlier Habsburg monarchy; its story began to be written much earlier than the modern nation-states of today’s Central Europe.

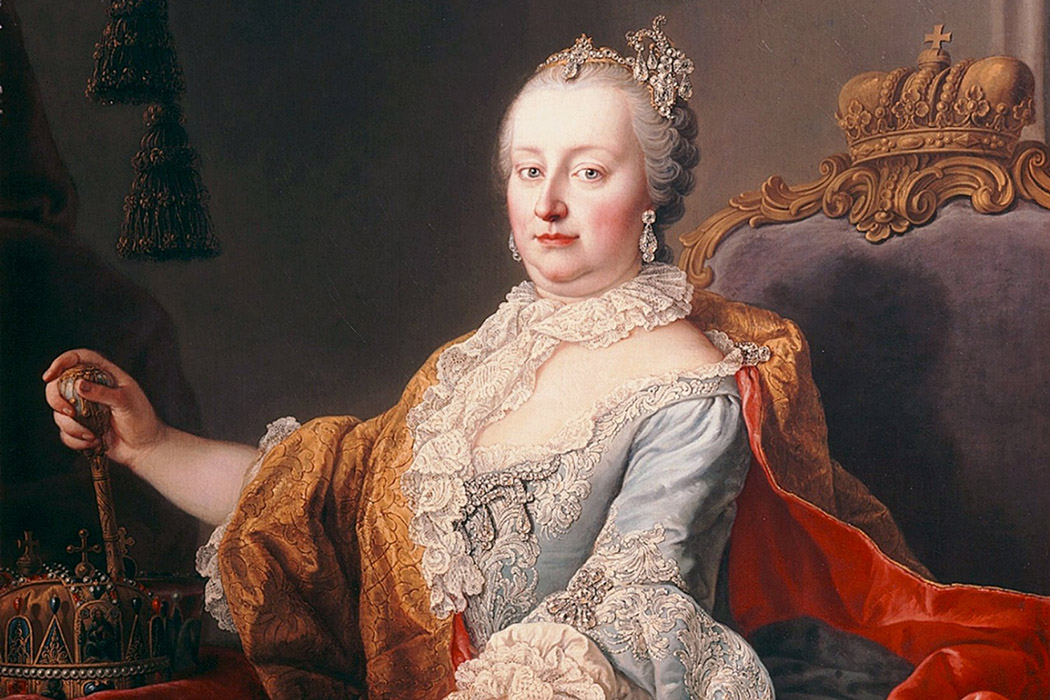

The first verified and official records of Blaufränkisch, come from the period when a special woman of the Habsburg family reigned in the vineyards of the Pannonian Basin:

Maria Theresa, Empress of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, Queen of Hungary, Czech Republic, Croatia and Slavonia, Archduchess of Austria and Piacenzy, Grand Duchess of Tuscany.

Origin of the name Blaufränkisch

Like other old varieties, Blaufränkisch has several names and synonyms, most of which are literally translated into the relevant national language. The most commonly used names are: Blaufränkisch (Austria), Frankovka modrá (Slovakia and the Czech Republic), Kékfrankos (Hungary), Limberger (Germany, France, Romania), Crna Frankovka (Balkan Peninsula), Frankonia Nera (Italy).

The origin of the name Blaufränkisch probably dates back to the Middle Ages, to a period when facts often merged with myths and legends into one whole. In addition, each region, each language, has its own names and interpretations. That is why it is sometimes difficult to seperate the Blaufränkisch of today from its myths and legends. We are more or less dependent on modern interpretations and one of them is as follows.

In the Middle Ages, the common people in the territory we now call Central Europe divided the vineyard (grapes) into two basic categories according to quality, or „nobility“.

Quality / noble varieties were marked as Frankish (fränkisch); lower quality, less noble varieties were marked as Hunnic (hunnisch or heunisch).

Today, we interpret these designations as meaning that the designation Frankish was derived from the word Franks. At the time, it was generally said among ordinary people that, thanks to Charlemagne and his codex, wine from the Frankish region was of very high quality.

Pivnica BRHLOVCE – Blaufränkisch 2021 – Wild Beauty

The name Hunnic was probably derived from the old Low German word for ‘large’, and in this case it refers to grape varieties with large berries, which provide higher yields than ‘Frankish’ varieties with smaller berries, but are of lower quality, more acidic and less concentrated in taste. The “Frankish” varieties probably achieved higher sugar content, as a result of which the wines from them subsequently had higher alcohol and at the same time had lower acids than the wines from the “Hunnic” varieties.

The terms “Frankish” and “Hunnic” were also used, for example, by the 11th-century mystic and botanist, St. Hildegard of Bingen. In one of her works she wrote that the wine of the “Frankish” varieties was stronger and set in motion the blood in the body so much that it had to be diluted with water, while the wine of the “Hunnic” varieties was more watery in nature and therefore need not be diluted with water.

Based on the social hierarchy of the society of that time, we can say that “Frankish” wine was intended for lords and “Hunnic” wine was intended for servants and peasants. Records from the beginning of the 14th century, for example, offer us the following caste view of the hierarchy of wine consumption: royal wine, men’s wine, wine for servants, peasant wine.

Probably at the end of the Middle Ages, the term ‘Schwarzfränkisch’ began to describe higher-quality red noble wines in the Pannonian Basin, which meant, among other things, wines with higher alcohol and lower acidity. However, we still have to regard these parameters, such as the amount of alcohol and the amount of acids, in the context of the Middle Ages and not compare them to today’s wines.

In the Middle Ages, it was common for things to be named in such a way that they were compared to a reference point and named after it. Identity and originality were perceived in a completely different sense than today. If the reference point for higher quality red wine was Franconian red wine, then often any higher quality red wine was named „Franconian“, which did not necessarily mean the same variety. It did not even necessarily mean the same specific style of wine. Quality red wines were associated only with the name – “Frankish red wine“.

Today, it is generally believed that the name Blaufränkisch /Frankovka modrá is derived from the word Schwarzfränkisch.

The Little Ice Age, the Ottoman occupation of Hungary and the Thirty Years’ War

In Europe, sometime around 1500, began the so-called Little Ice Age. The average annual temperature fell by almost two degrees Celsius in ten years. For viticulture and winemaking, but also for all agriculture in the Pannonian Basin, this cooling had a catastrophic impact in the long run, bringing hunger and natural disasters.

In addition, on the 29th of August, 1526, in the city of Mohács about 180 km south of Budapest, the Battle of Mohács occurred, in which the troops of the Ottoman Sultan Süleyman I defeated the Hungarian army of King Louis II. Jagelovsky. Subsequently, the Ottoman troops entered Hungary and occupied most of its territory until 1697. During this period, in the years 1618 – 1648, another great religious / power conflict took place in Europe – the Thirty Years’ War, in which the Catholic Habsburgs fought against Protestants, a conflict that completely affected Central Europe.

These political and military conflicts did not help the development of viticulture and winemaking in the Pannonian basin; on the contrary, they often harmed it. Viticulture and winemaking thrive in peaceful years, when economic and political stability allows the development of long-term projects and investments.

A peaceful change did not happen until after 1700 when, after two hundred years of political and military conflicts, a major reconstruction began – the restoration of the Habsburg monarchy which culminated on 25. June 1741 in today’s Bratislava, in the Cathedral of St. Martin with the coronation of Maria Theresa as the Hungarian queen. Subsequently, the golden era of the Habsburg monarchy occurred.

Along with political changes, there came a gradual warming to end the Little Ice Age during the same period. The rapid development of viticulture and winemaking in the Pannonian Basin is also associated with this warming. From 1748, a major restoration of vineyards started in Austria-Hungary and their area reached the level before the Thirty Years’ War. As a result, at the turn of 18th and 19th centuries, in some areas of the Habsburg monarchy the land under vine reached its historic high.

First mentions

A popular legend says that Blaufränkisch was brought to Austria-Hungary by Francis- Stephen Lorraine, husband of Maria Theresa. Francis I lived from 1708 to 1765 and came from Lorraine (part of today’s France) to marry then- Archduchess Maria Theresa in 1736. He was a very talented and successful businessman, and an enthusiastic botanist. Before he married, he made a great journey through Europe between 1731 and 1732, where he gained a lot of inspiration for his later business.

One of the legends says that cuttings of Blaufränkisch came to the Habsburg Empire during the travels of Francis-Stephen Lorraine from Western Europe. However, modern research into the DNA of Blaufränkisch today clearly shows that Francis I could not have brough vine cuttings identical to today’s Blaufränkisch from Western Europe. The genetic origin of the Blaufränkisch is in fact from the territory of the Pannonian Basin.

However, Francis I certainly met quality red wines in his homeland, Lorraine, and later on his travels in Western Europe. As a gifted businessman, he had to notice that quality red wines were more expensive than white wines and brought higher profits. He was probably more of a spiritual father during the great restoration of vineyards in Austria Hungary of the idea to plant, where it was the appropriate climate, “Schwarzfränkisch“, red noble varieties with smaller berries at the expense of the more lucrative “Hunnic” varieties which gave wine of lower quality,

Another legend, in which “Schwarzfränkisch” is mentioned, states that in 1767 the imperial family of Maria Theresa contracted smallpox. It was at that time that the pastor of Bratislava, specifically from today’s urban district of Rača – named Radochányi, sent Maria Theresa a barrel with “Schwarzfränkisch” as a birthday present. And allegedly, it was “Schwarzfränkisch” from Rača that helped her recover.

The fact that “Schwarzfränkisch” from Rača Maria Theresa really cured is debatable, but the verified fact is that 27. June 1767, just a few days after Maria Theresa recovered, she personally received a delegation of parishioners from Rača in Vienna, headed by the pastor of Radochányi. She donated a golden chasuble to the pastor, and in the same year, by decree, she confirmed to the inhabitants of Rača the right to grow the “Teresian Rača Schwarzfränkisch”, and in addition reduced their part of a wine tax.

In 1777, Sebastian Helbling, one of the first ampelographers in Austria-Hungary, in his work Beschreibung der in der Wiener Gemeinen Weintrauben-Arten also specifically mentions that the best red variety in Lower Austria is the “Schwarz Fränkische”.

In 1837, in his work “Systematic Classification and Description in the Austrian Weingärten vorkommenden Traubenarten“, Johann Burger also mentioned the variety “Schwarz Fränkische”

Both Sebastian Helbling and Johann Burger, in their works they mention the “Schwarz Fränkische“, but neither describes it in detail, nor offer detailed pictures of leaves, canes or grape bunches. Therefore, we can still only argue what variety or varieties under the name “Schwarz Fränkische” actually mean.

The official origin of the Blaufränkisch and its genetic origin

For the first time, Blaufränkisch was officially and thoroughly documented only in 1862, at a wine exhibition in Vienna. Subsequently, in 1875, the International Ampelographic Commission in Colmar, France, adopted the name Blaufränkisch as the official name for the detailed red variety, which we still know under this name. In the territory of today’s Hungary, this variety is first officially mentioned as Kékfrankos in 1890.

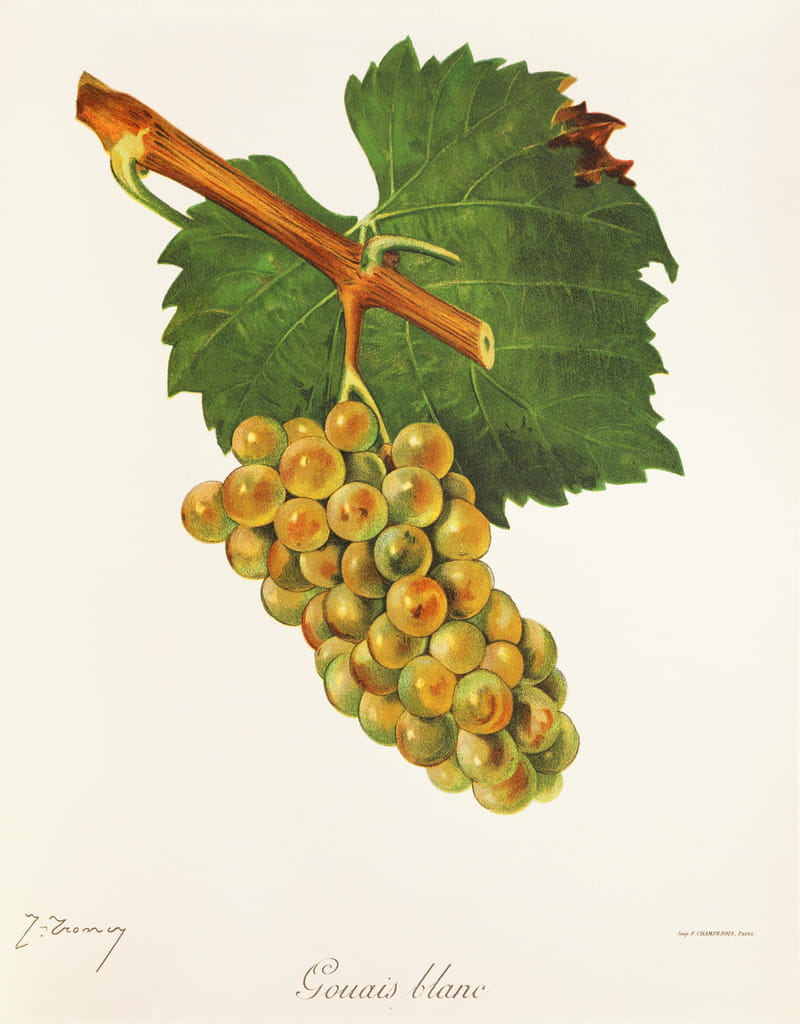

Modern DNA analyses have revealed that the parents of Blaufränkisch are the varieties Gouais blanc and Blaue Zimmettraube. Gouais blanc (French name) or Heunisch weiss (German name) is an ancient white vine variety that is now grown only in small areas, mostly in Eastern Europe. Throughout the Middle Ages, it was one of the most cultivated varieties in Europe. It did not provide too high quality wines but had high yields and was easy to grow. It was grown mainly by serfs.

The name “Gouais” is derived from the old French adjective gou, which was a derisive term implying to the variety and its wine that it served as inferior drinking for peasants. However, the humble Gouais blanc, together with the varieties Tramín and Pinot, is now considered the basis of modern Central European varieties.

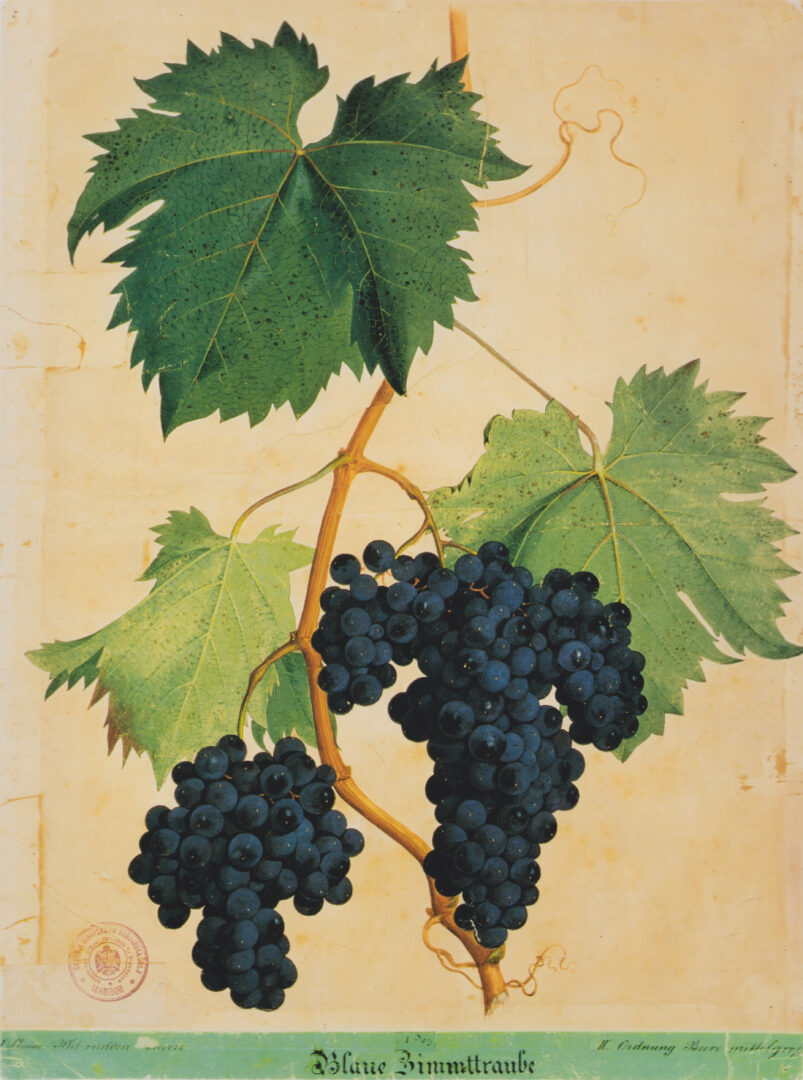

Blaue Zimmettraube is now an almost extinct red variety. In the past, this variety was grown mainly in Lower Styria, in the territory of today’s Slovenia. And it is Styria today that is also considered to be the place where the varieties Gouais blanc and Blaue Zimmettraube naturally crossed, which gave rise to Blaufränkisch as we know it today.

Phylloxera and Blaufränkisch

At the turn of the 1870s and 1880s, phylloxera attacked the Austro-Hungarian vineyards. The vine phylloxera, a small, parasitic aphid, infests the roots of a vine, where it forms dark, small and malignant tumours which cause the gradual death of the entire plant.

The central authorities of the Habsburg Monarchy were well aware of the gravity of the situation and paid considerable attention to the problem. The old, indigenous European varieties were hardly resistant to phylloxera at all. Only the breeding of new grape varieties was able to resist this insidious pest. Therefore, entirely new American rootstock vines were bred on a large scale, with which new, more resistant vines were subsequently planted.

However, the process of planting new vineyards was not a simple process and was heavily subsidised by the Habsburg Monarchy. As we know well from history, where there are large state subsidies, there is also large corruption. It would be naive to believe that the planting of new, more resistant vineyards was any different in Austria-Hungary.

At that very moment, when new, more resistant vineyards were being planted on a large scale in Austria-Hungary, Blaufränkisch arrived upon the viticultural map of Central Europe in style. Until then, the more or less little-used, scientifically undescribed blue variety began to be planted on a massive scale, gradually becoming the most widely planted blue grape variety in Central Europe. Today we can say that Blaufränkisch emerged as a winner from the great transformation of the vineyards after phylloxera.

The modern history of Blaufränkisch

We must say that in Central Europe in the twentieth century, Blaufränkisch was – and still often is – considered a common, light and uncomplicated, inexpensive wine. For a long time in its homeland, Blaufränkisch wine simply wasn’t synonymous with structured, sophisticated, valuable, higher-priced wines.

It has to be said that there were, or still are, a number of reasons for this. The first reason is found in the vineyard. Blaufränkisch can yield a lot, and this is still used, even abused, in vineyards today, whether in Austria or in Slovakia. Especially in the past, in the vineyards, it was the quantity, with the words “but it’s only Blaufränkisch”. Simply, that was the time. In the socialist period, quantity was more important than quality.

Another factor that fundamentally influences the structure of Blaufränkisch wine is ageing in wooden barrels. Blaufränkisch often has higher acidity and therefore also needs time and cellaring to show its potential, its subtle yet refined structure. And Central European winemakers, unlike French or Italian winemakers, have historically not had much experience with longer maturation in quality wooden barrels. On the contrary, young wines were drunk in bulk.

A third factor influencing the opinion of Blaufränkisch is the Central European inferiority complex about red wine. The powerful, high-alcohol, low-acid red wines from the south of Croatia, Italy or Spain have always simply charmed Central Europeans and are still often synonymous with ‘proper’ or ‘real’ red wine. This comparison of climatically and geographically different wines has led many Central European wine drinkers to the mistaken belief that it is impossible to make a ‘good’ red wine in Central Europe.

The truth is that Blaufränkisch can be an interesting and characterful red wine with finesse, and it is also true that it will always be a different red from the south. But this is all a question of identity and self-awareness of who we are, what we stand for and where we are going. And perhaps the way Central Europeans often fail to embrace Blaufränkisch and its fresh character may in fact be more about how they fail to embrace themselves, their own otherness and uniqueness, shaped by their own turbulent history.

From a climatic point of view, Blaufränkisch seems to fly towards two extremes. In the more southerly wine-growing areas, particularly in southern Hungary, where the climatic conditions allowed it, Blaufränkisch was often overlooked. The wines were then jammy, with higher alcohol and no fresh character. In more northern areas, Blaufränkisch was often too acidic and “green”.

In the 20th century, there seemed to be a lack of balance between these two extremes. Moreover, in the late 1990s, the fashion for barrique casks came to Central Europe. Austrian winemakers were the first to take to it in a big way. The result was barriqued Blaufränkisch. Another extreme.

Blaufränkisch has had to go a long way in finding its identity. The skin of the grape is thicker compared to Pinot Noir. The growing cycle in the vineyard lasts 150 days at a sum of active temperatures of 2900 °C. It can be characterised by early budding, late ripening and very high yields thanks to its vigorous growth. These characteristics do not make life easy for wine growers.

Spring frost is the enemy of early budding. Late ripening in autumn rains, in turn, carries the risk of fungal infections and insufficient ripening. On the other hand, the long growing season facilitates the creation of an incredibly rich aromatic structure. At lower yields, it can again impress with its structure, but not at the expense of freshness and lightness.

The fundamental change for Blaufränkisch came only at the turn of the millennium, when a small handful of winemakers from the former Habsburg monarchy began to realise its true character and understand where its balance lay. These winemakers, unlike their predecessors, discovered that Blaufränkisch was not destined for heavy, alcoholic wines heavily influenced by heavily-fired oak barrels.

Blaufränkisch is the red variety most like white wine in its structures, flavors, and “behavior”. Blaufränkisch’s crisp acidity and medium body allow it to express its character powerfully and intensely. In a world of heavy, characterless, alcoholic wines, of which the world is full today, it can therefore charm with its lightness, freshness and refinement.

Thanks to its acids, it has great potential to age in the bottle. It can therefore offer patient wine lovers a rich and refined world of tertiary aromas and flavours after years. Conversely, young wines that have not been on the skins for long literally astonish with their, in a good sense of the word, primary fruitiness, their seductiveness. And with Blaufränkisch, one should certainly not forget the rosé.

Yes, rosé is still often thought of as a second-rate wine, but for some varieties, rosé makes a lot of sense. And Blaufränkisch, with its higher acidity and medium body, is one of the most suitable varieties for rosé. And when a rosé made from Blaufränkisch is made as a sparkling wine, the experience is enchanting.

But is Central Europe ready to accept Blaufränkisch for what it is? Can Central Europe embrace its complicated yet rich Austro-Hungarian past? Blaufränkisch unites Central Europe culturally, historically and sensorially, not divides it. This is its great added cultural and social value.

Blaufränkisch is a unique autochthonous (local) variety of the Pannonian basin, which is mostly grown and processed by small to medium-sized wine-growing and wine-making enterprises. This fact is crucial given that autochthonous varieties are playing an increasingly important role in global wine consumption, which is perhaps a natural reaction against the McWine phenomenon, a reaction against uniform wines without any individuality, without any added value.

Today, Blaufränkisch is subtly, but with refinement and freshness, entering an international wine scene tired of heavy wines. Let us see how it can assert itself in the 21st century, where originality and uniqueness are particularly valued in the world of wine.

Grilled goose breast and Blaufränkisch from Tekov

A well-fed goose used to be the pride of the farmyards in Region Tekov (Slovakia, district Levice ) and roast goose was not to be missed at family celebrations. In the past, whole quarters of goose were even sold at autumn fairs in Levice and foie gras from Tekov was exported all over Europe.

Nowadays, however, it can be a challenge to obtain a locally raised goose to roast and eat. Not only financially, but also in terms of quantity. For those who enjoy goose meat, preparing goose breast on the barbecue itself may be the solution. Goose (but also duck) meat acquires a specific flavour through roasting, which is why we do not recommend the sous-vide technique for its preparation.